Atmospheric turbulence mitigation in wide-field astronomical images with short-exposure video streams

Spencer Bialek  1,2, Emmanuel Bertin

1,2, Emmanuel Bertin  2,3, Sébastien Fabbro

2,3, Sébastien Fabbro  1,4, Hervé Bouy

1,4, Hervé Bouy  5,6, Jean-Pierre Rivet

5,6, Jean-Pierre Rivet  7, Olivier Lai

7, Olivier Lai  7, Jean-Charles Cuillandre

7, Jean-Charles Cuillandre  3

3

1Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, V8W 3P2, Canada

2Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope, Kamuela, HI 96743, USA

3AIM, CEA, CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Cité, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France

4National Research Council Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics, Victoria, BC, Canada

5Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux, CNRS and Université de Bordeaux, Allée Geoffroy St. Hilaire, 33165 Pessac, France

6Institut Universitaire de France

7Université Côte d’Azur, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, CNRS, Laboratoire J.–L. Lagrange, F-06304 Nice Cedex 4, France

Abstract

We introduce a novel technique to mitigate the adverse effects of atmospheric turbulence on astronomical imaging. Utilizing a video-to-image neural network trained on simulated data, our method processes a sliding sequence of short-exposure (∼0.2s) stellar field images to reconstruct an image devoid of both turbulence and noise. We demonstrate the method with simulated and observed stellar fields, and show that the brief exposure sequence allows the network to accurately associate speckles to their originating stars and effectively disentangle light from adjacent sources across a range of seeing conditions, all while preserving flux to a lower signal-to-noise ratio than an average stack. This approach results in a marked improvement in angular resolution without compromising the astrometric stability of the final image.

The problem

Atmospheric turbulence causes the wavefront of incoming light to be dynamically distorted. As a result, long exposures taken from ground instruments lead to the degradation of images and the overall effect can be framed as a blurring operation. With small telescopes (aperture ≈ 3 − 4 times the Fried parameter), the tilt component of the wavefront distortions outweighs the sum of all other contributions, and the effect of turbulence is prominently random image motions on the focal plane.

As the video above shows, fast imaging provides much sharper images than long exposures, but the high-resolution information is scrambled by turbulence. To compensate the effects of atmospheric turbulence over wide fields, one could imagine correcting those apparent motions by adjusting a “rubber” focal plane model (Kaiser et al. 2000), which consists of a distorted virtual pixel grid.

For deep sky observations, which are our primary goal, the deformations of this virtual grid would have to be continuously controlled by a number of guide stars over its surface. However this process is complex to set up in practice, e.g., changing conditions require dynamic adaptation of the statistical model, and the number of individual stars suitable for guiding is often insufficient. Instead, we propose to leverage the power of Deep Learning to directly reconstruct virtual exposures from video sequences.

The method

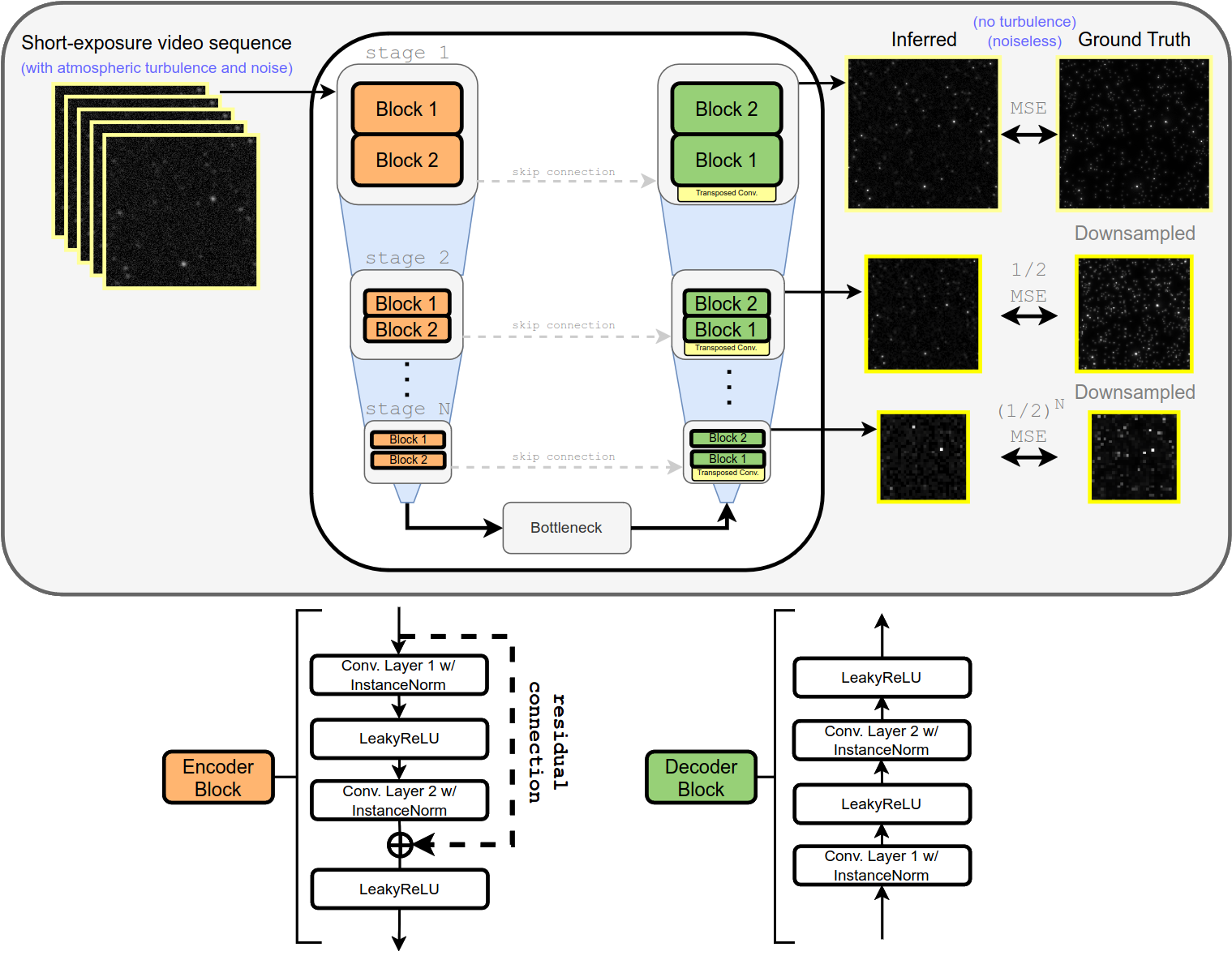

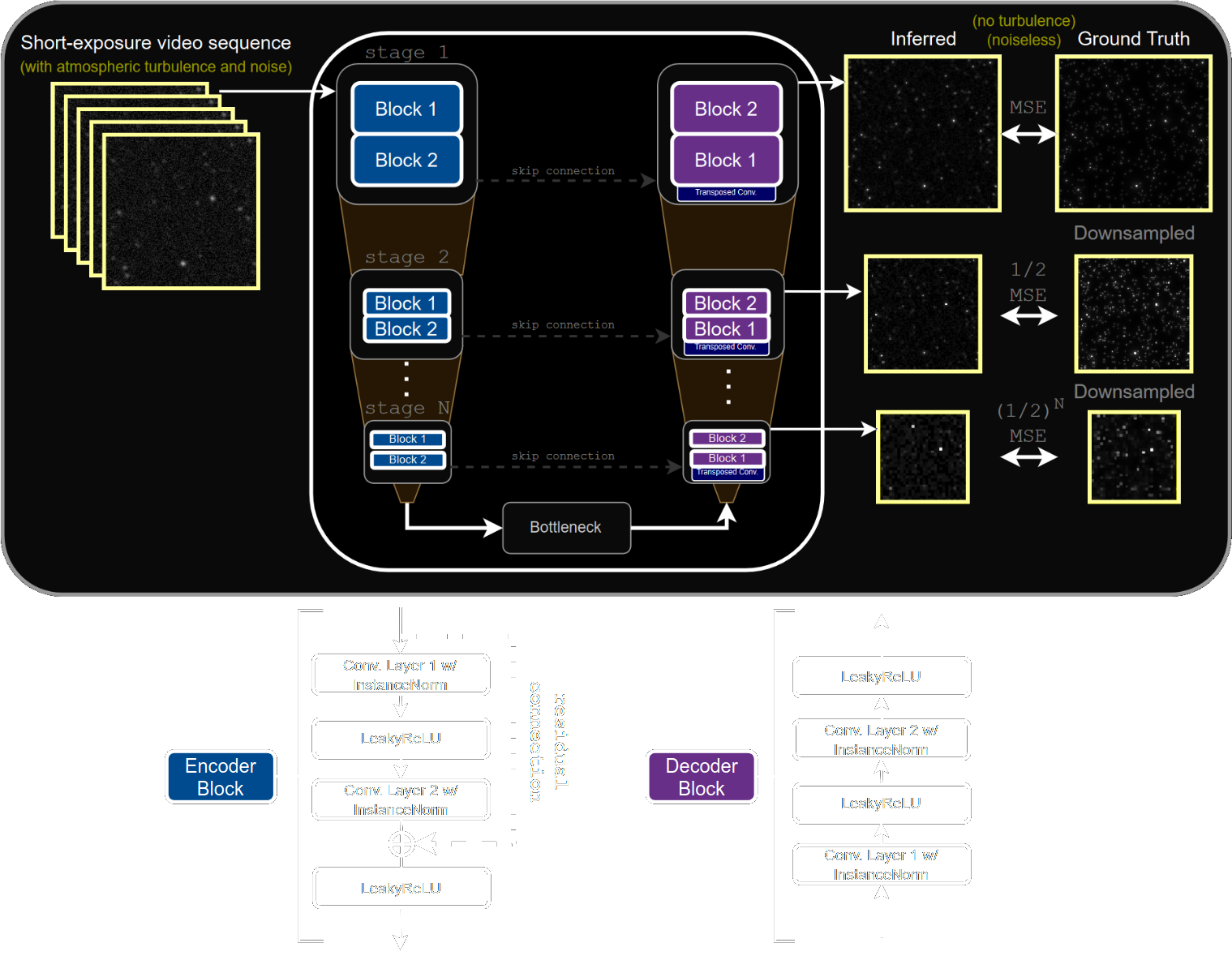

The cornerstone of our proposed method is the application of the Residual U-Net, a variant of the traditional U-Net neural network architecture known for its proficiency in semantic segmentation and image reconstruction tasks. A set of simulated short-exposure video streams of stellar fields – with turbulence and noise – along with their corresponding ground truth frames – with no turbulence or noise – is used to train the model. Instead of a single output, the model additionally has outputs from each stage in the decoder which are compared to downsampled versions of the ground truth using a weighted mean-squared error (MSE) loss function. Once trained, either a simulated or real video stream can be used as input and only a single (not downsampled) inferred image is retrieved.

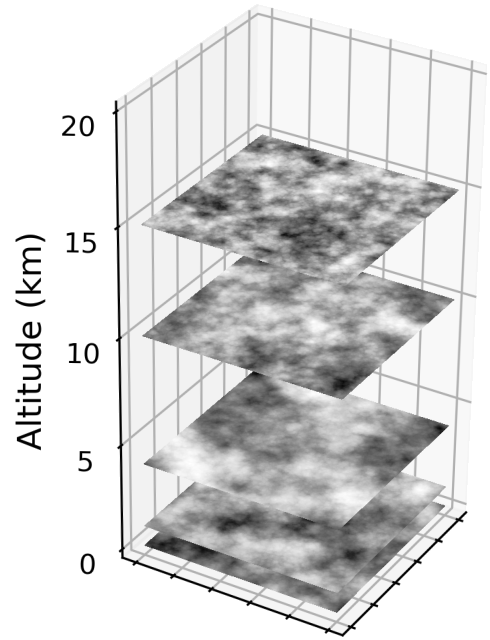

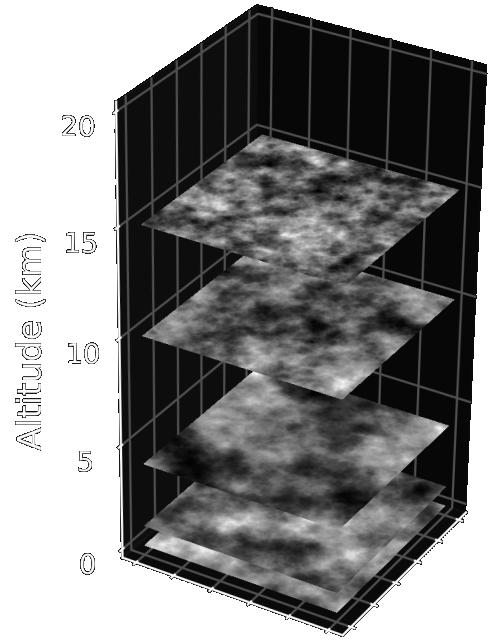

Training of the neural network is done purely on image simulations. We decompose the atmosphere into discrete layers which perturb the wavefront of the light from each star as it passes through. The entire simulation pipeline is written with PyTorch so that GPUs could be maximally utilized with Fast Fourier Transforms. This results in the capability to render ∼150,000 point sources per second, which is a couple orders of magnitude faster than other similar implementations.

We generated training datasets containing 40,000 6- and 12-second video sequences; 12 seconds was eventually chosen as a compromise between GPU memory constraints and collecting enough information about the turbulence and faint stars. Each frame matches the properties of the wide-field camera at the C2PU Omicron Telescope. Along with each video sequence, we generated the corresponding ground truth frame in which we disabled contributions from the atmosphere and any sources of noise in our simulation pipeline.

Results

Synthetic data

Visually, the proposed method does an excellent job at taking in a short sequence of turbulent images and producing clear, sharp, noise- and turbulence-mitigated images.

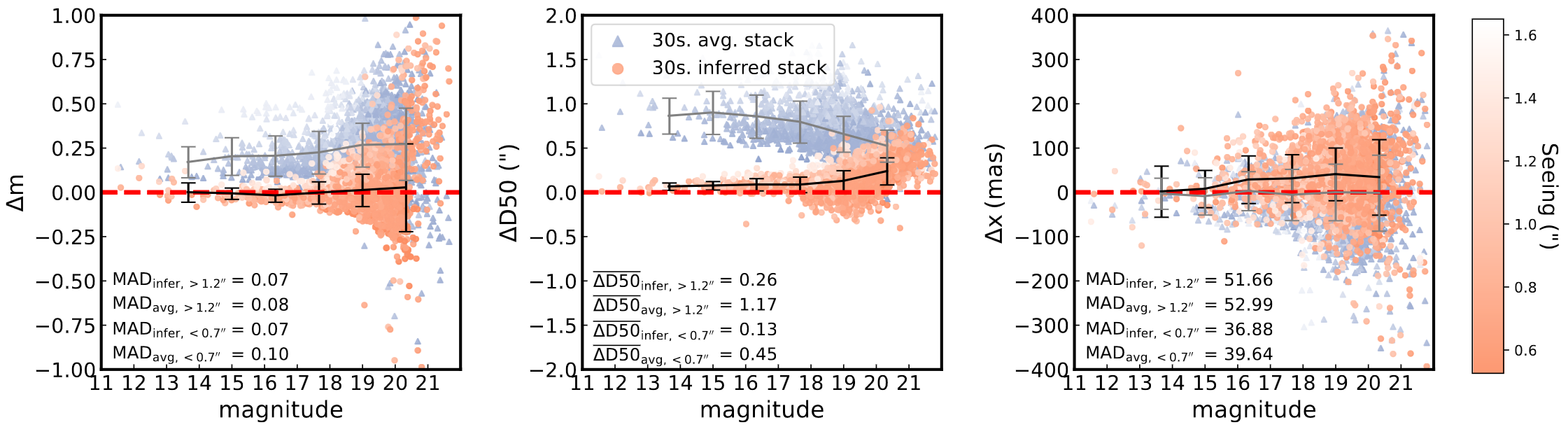

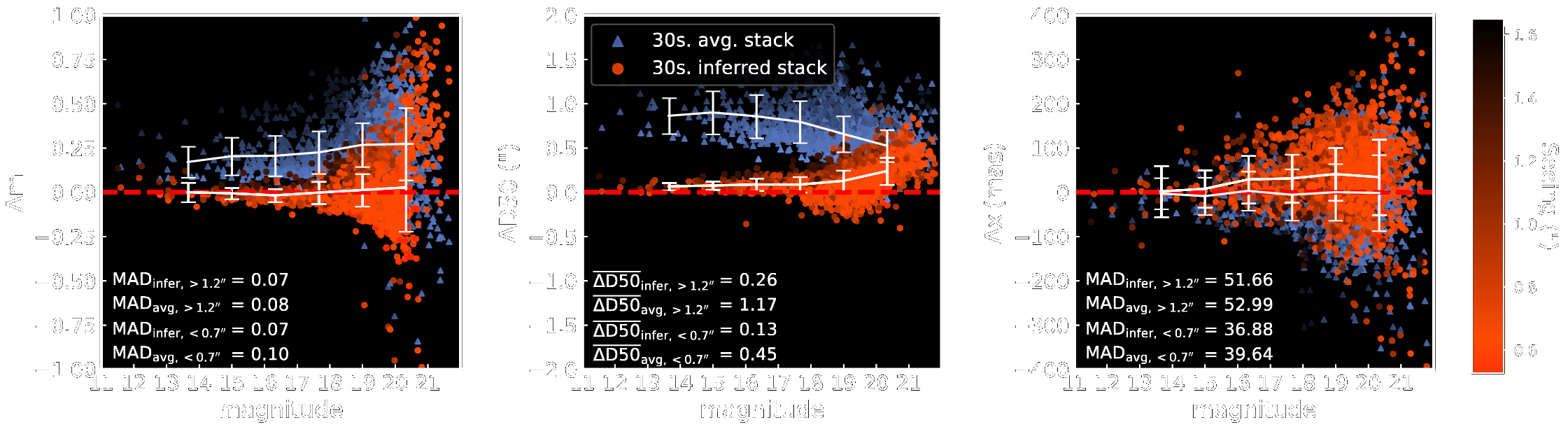

A series of quality assurance tests were made to validate the image reconstructions made by the U-Net. Hundreds of 30-second simulated observations of random stellar fields, with varying seeing conditions, were created and two images were made for each example: a stack made from the U-Net inferred images and a simple averaged stack of the raw frames.

Real data

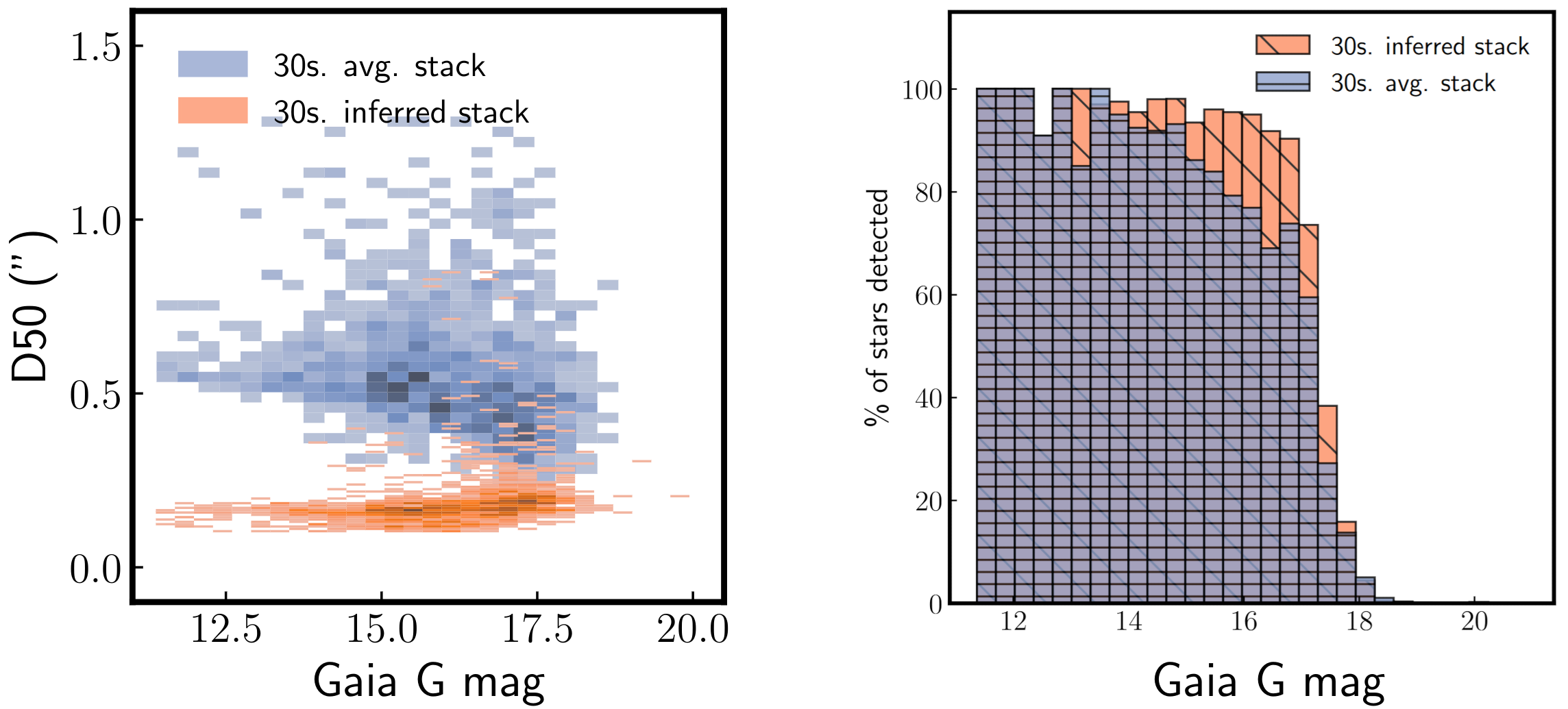

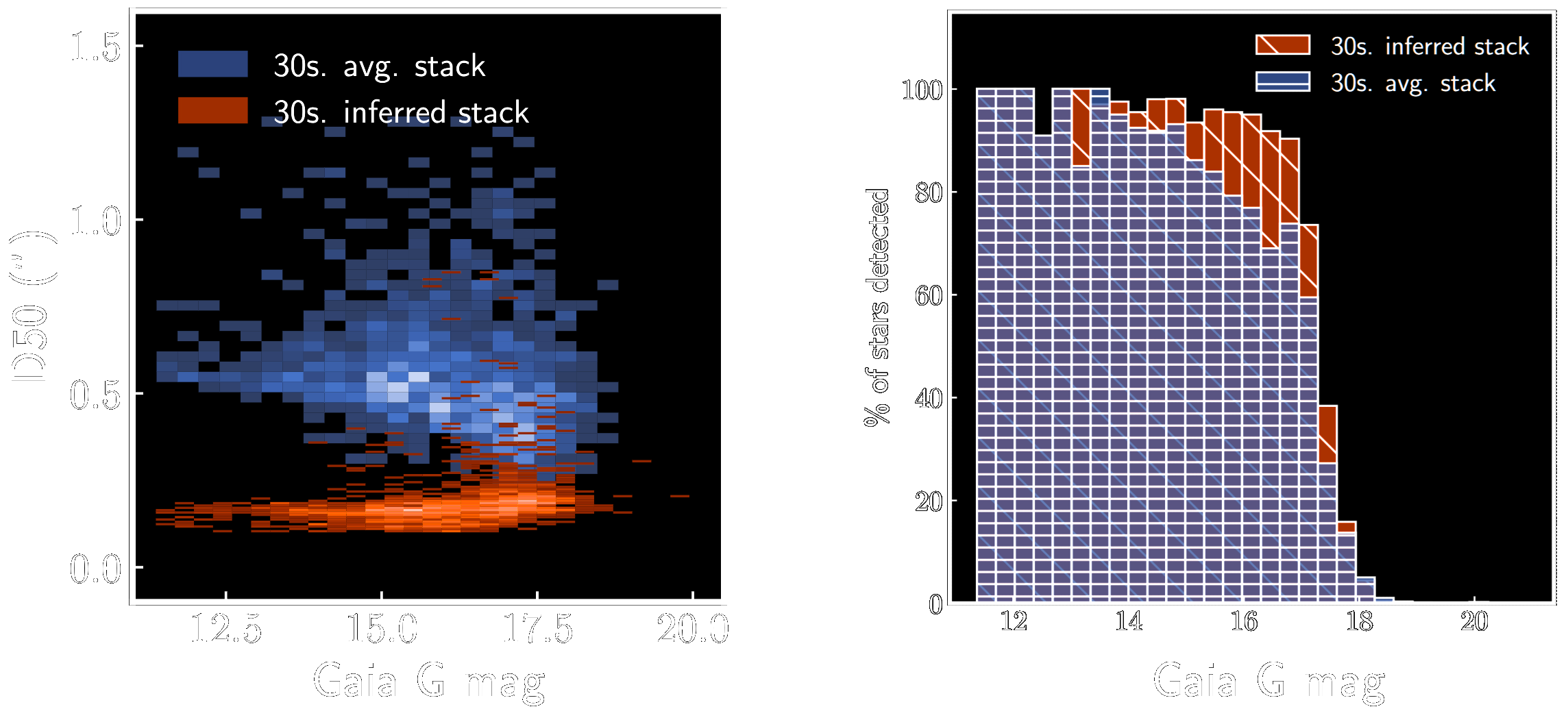

We directly applied the neural network trained from synthetic data to real video sequences taken at the prime focus of the C2PU 1m “Omicron” telescope (Calern observatory, France) without transfer learning or domain adaptation. As the illustrations below show, the proposed method is directly applicable to real video sequences, and provides a marked improvement over regular image stacking, both qualitatively and quantitatively. The inferred frames exhibited a typical 2.5\(\times\) reduction in D50 measurements, and more than 30% more stars are identified relative to the averaged frame.

Conclusion

Our method, trained on simulated observations, is adept at inferring a turbulence- and noise-free image from a sequence of short-exposure observations of a stellar field, effectively associating speckles with their source star and disentangling light from proximate sources, while conserving flux. However, it is important to acknowledge that further development and refinement are necessary for this approach, particularly in recovering fainter sources in low stellar density environments, improving astrometric precision, and reconstructing the images of extended objects such as galaxies.

Checkout the full paper.